The market valuation of Oil and Gas Investment companies collectively referred to as ‘Big Oil‘has long been a focus of financial debate. While they were traditionally considered the backbone of the world economy, their share prices have seen stagnation and decline over the past decade.

Some analysts attribute this to ESG (environmental, social and governance) pressures, while others point to fracking technology and OPEC’s strategic weakness. But the truth is far more complex. The future of Big Oil and Gas Investment is the outcome of several geopolitical, technological, and environmental battles playing out simultaneously.

This article will shed light on these aspects based on extensive research and try to understand what factors will determine whether oil companies remain a ‘safe investment’ in the next decade or not.

ESG: A Persistent Pressure, Not a Temporary Trend

The article states that “it would be wrong to consider ESG merely a trend,” and research confirms this.

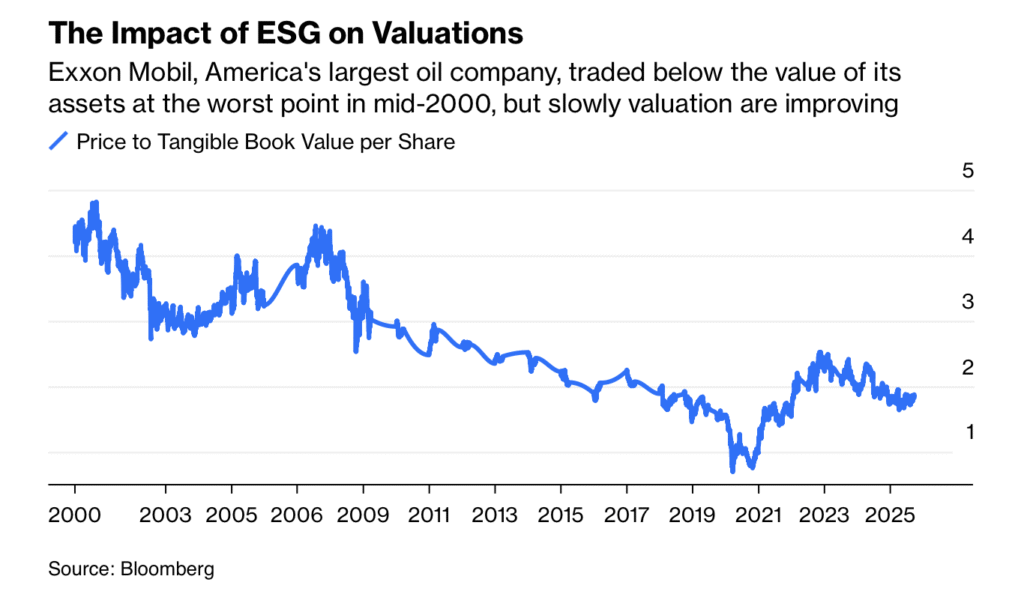

Investor exodus: The world’s largest asset managers, such as BlackRock and State Street, have publicly acknowledged climate risks as a financial threat. In 2021, a small hedge fund, Engine No. 1, secured the appointment of three members to ExxonMobil’s board by raising ESG issues, proving that investor activism has become a powerful weapon.

Regulatory pressure: The EU’s ‘taxonomy’ and the SEC’s proposed climate risk disclosure rules in the US have paved the way for holding companies accountable. Companies will now have to prove they are aligned with long-term climate goals, or they will face difficulties raising capital.

Result: ESG is no longer just an issue of ‘image building’. This is directly affecting a company’s cost of capital and the sustainability of its long-term business model.

Fracking and OPEC: A Moving Chessboard of Geopolitics

The American shale oil revolution, backbone of which is hydraulic fracturing technology, shattered OPEC’s monopoly over the past decade. But this balance is delicate.

Cost sensitivity of fracking: Shale oil production declines much faster than conventional Oil and Gas Investment wells, requiring the constant drilling of new wells and significant investment. When oil prices collapsed in 2020, more than 100 US shale oil companies went bankrupt. This indicates that if environmental regulations tighten or funding becomes more expensive, US production could decline sharply.

The Growing Role of OPEC+: The Russia-Ukraine war showed the world that the importance of OPEC+ (OPEC + Russia) increases again in times of geopolitical crises. In 2022, when prices surged past $130 a barrel on fears of sanctions on Russian oil, Big Oil companies made record profits. It is clear that any reduction in supply could temporarily make OPEC a ‘price setter’ again.

Result: The cost of fracking and the politics of OPEC+ create a conflict for oil prices. While technological advances have made fracking cheaper, any major geopolitical shock could alter this balance.

Impact on the Middle East Economy: A Domino Effect

Falling oil prices have a direct impact on the economies of oil-exporting countries.

Saudi Arabia’s ‘Vision 2030’: Saudi Arabia, which derives more than 90% of its revenue from oil, has launched ‘Vision 2030’ to reduce its dependence on oil. It aims to diversify into sectors such as tourism, entertainment and technology. High oil prices boosted his budget surplus to a record high in 2022, but falling prices in the 2014-16 and 2020 periods pushed him into deep deficits.

The difficulties in Iraq and Angola: Countries like Iraq, where social welfare programs and infrastructure development are entirely dependent on oil revenues, are facing budget deficits. This instability directly fuels fluctuations in the global energy market.

Result: Falling oil prices affect not only Big Oil and Gas Investment companies, but also the economic and social stability of entire countries, creating uncertainty in the global economy.

India and China: New Centers and Challenges of Energy Demand

As the article states, energy demand is growing rapidly in emerging markets like India and China, but this demand is no longer limited to conventional oil.

China’s dual strategy: China is the world’s largest Oil and Gas Investment importer, but it has also become a world leader in renewable energy and electric vehicle production. China has set a target of carbon neutrality by 2060 and is rapidly moving from coal to solar and wind power for its energy security.

India’s ‘Panchamrit’ scheme: India set a net-zero target by 2070 at COP26 and pledged to meet 50% of its energy needs from renewable sources by 2030. Companies like Tata and Reliance are investing heavily in electric vehicles and green hydrogen.

Result: These markets represent the last major opportunity for Big Oil and Gas Investment, but even here they will face direct competition from renewable energy and electric vehicles. Companies that do not understand this change will lag behind in these markets as well.

Energy Transition: Big Oil’s Last Option

The race to net-zero targets has presented Big Oil with a choice of ‘transform or die’.

BP and Shell vs. Exxon and Chevron: European companies such as BP and Shell have moved to transform themselves into ‘energy companies’. BP has set a target of cutting oil and gas production by 40% and increasing renewable energy capacity 20-fold by 2030. Meanwhile, US companies Exxon and Chevron are still primarily focused on fossil fuels, although they are now experimenting in areas such as carbon capture and bioenergy.

Investment trends: According to Bloomberg NEF, Oil and Gas Investment in the global energy transition are expected to reach $1.1 trillion in 2022, equaling investments in fossil fuels for the first time. This is a clear indication that the flow of capital is now rapidly moving towards renewable energy.

Upshot: Big Oil and Gas Investment future will depend on how quickly and effectively they can transform their business model. Companies that achieve leadership in clean energy, green hydrogen, and carbon capture technologies will gain investor confidence and higher valuations.

Conclusion: What is the way out for investors?

Considering oil as a ‘safe investment’ over the next 10 years could prove to be a risky bet. As the article points out, in the short term, geopolitical tensions and supply shortages could cause oil prices to surge and Big Oil companies to make profits. This may provide temporary trading opportunities for investors.

However, from a long-term perspective, the direction is clear. The global energy transition, net-zero policies, and the ever-increasing cost of renewable energy are the key factors that will determine the future of Big Oil and Gas Investment. ESG has become a persistent pressure, and OPEC is a geopolitical variable that will continue to influence the market from time to time.

Therefore, a better strategy for a prudent investor would be to view Big Oil and Gas Investment companies only as a short-term cyclical bet, while building a long-term portfolio by investing in companies and technologies that are laying the foundation for a clean energy future. Ultimately, the companies that adapt to the broader scope of ‘energy’ will be the ones that will stand the test of time.